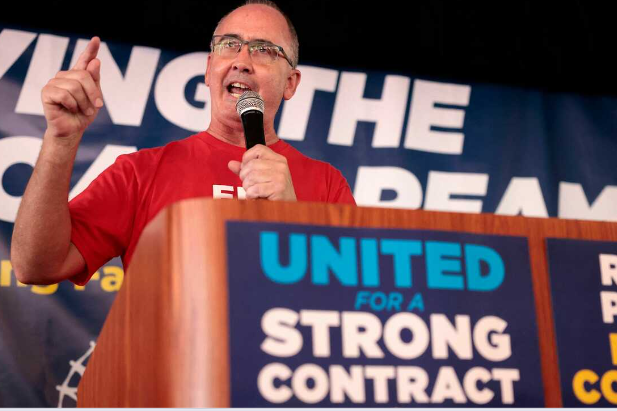

Workers at Stellantis, Ford, and General Motors plants secured monumental contracts that United Auto Workers president Shawn Fain called “a major victory for our movement.” This came after a wave of nationwide strikes in September and October that saw over 45,000 of the UAW’s 150,000 auto workers walk off the job. Among other things, the contracts:

- Secured an immediate 11% wage increase and a 25% increase in base pay over time by 2028. The wage increases will eclipse all raises for employees at America’s Big Three automakers from 2001-2022 combined.

- Converted thousands of temporary workers to full-time employees.

- Restored cost-of-living allowances (COLA) that got cut after the 2008 Recession.

- Cut the time it takes for a worker to reach top pay by 62%.

- Workers at Ford and Stellantis killed the two-tiered pay system.

Other automakers have responded quickly. The Japan-based manufacturers Toyota and Honda have announced they will raise pay for their American factory workers by 9% and 11%, respectively. South Korea’s Hyundai will raise pay by 25% over the next four years, matching the increases won by the UAW. All three companies announced their pay raises after the UAW reached a tentative agreement with GM and before workers at any company ratified contracts.

Perhaps these companies are just trying to stay competitive with wages at the Big Three. More likely, though, they are afraid of rising union power. They feel the pressure of organized labor and are trying to appease their workers so they will not unionize.

“They could have just as easily raised wages a month ago or a year ago,” Fain said during a video conference about the pay raises at Toyota. “They did it now because the company knows we’re coming for ’em.”

Their fear of organizing is not entirely unfounded. The UAW has explicitly stated that it aims to organize employees at thirteen auto companies, aiming at Tesla especially. Elon Musk, the CEO of the electric vehicle manufacturer, has long been the subject of scorn from labor activists due to his vocal opposition to unions.

“One of our biggest goals coming out of this historic contract victory is to organize like we’ve never organized before,” Fain said. “When we return to the bargaining table in 2028, it won’t just be with the Big Three, but with the Big Five or Big Six.”

The UAW’s union drive may be an uphill battle. Many of America’s non-union plants are in Southern states with conservative governments and right-to-work laws. Even in labor-friendly states like California, workers struggle to unionize non-union plants. Foreign automakers and EV startups are notoriously hostile to union efforts. Numerous failed attempts to organize workers at these plants haunt the UAW.

Conditions may be more favorable for the UAW now, however. Public support for unions is at an all-time high. The strike’s success has been highly publicized. And Shawn Fain has swiftly made a name for himself as a strong, passionate, and charismatic leader.

A UAW spokesperson said that workers at thirteen non-union automakers contacted the union seeking support in organizing their workplaces. Over a thousand workers at a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga signed union authorization cards last week.

Union membership has been on the decline since the 1980s. In 1954, more than a third of American workers were union members. Today, less than 10% are. The effects of this decline are not hard to see. Economic inequality has worsened, squeezing the middle class while young people and seniors are left behind. People are more apathetic and hopeless than ever. If all this is to be reversed, unions have to step up their game. Leaders need to be ambitious and passionate and able to energize workers into fighting for their futures.

Thankfully, unions are waking up to this reality. For decades, corrupt hacks and people without drive have led unions. This era of weak leadership is finally ending as leaders like Sean O’Brien of the Teamsters, Amazon Labor Union’s Chris Smalls, the IUPAT’s Jimmy Williams, and many others have risen to power. These figures have become well-known as critics of weak, ambitionless leadership. They are militants championing reform and intersectionality. Williams, for example, is a staunch advocate for immigrant workers and other underrepresented groups. O’Brien presided over contract negotiations with UPS last summer and forced the delivery service to make immense concessions at the threat of a paralyzing strike.

Fain, too, is a man with a can-do attitude and zero tolerance for weakness. His push to unionize the entire auto industry proves that. It may be difficult, but Fain and the UAW are fierce and gearing up for a fight. Fain is positioning himself as a role model for union leaders everywhere.

“I want expectations f-ing high. I want them through the roof,” Fain said. “We should have high expectations because we’ve made a habit of aiming low and selling lower and we’ve got to get away from that.”